#433 – How to become great in the age of AI

Today, I'm trying something a little different.

A longer essay on some thoughts I've been thinking, some people I've been learning from (old and new) and some ideas to help you interpret and navigate the future.

Foreword

The future belongs to those who read the original sources.

Your job is to click the links, watch the clips, roll up your sleeves and explore...

How to Become Great in the Age of AI

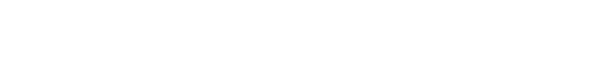

We're in the Clip Art age of AI.

Meaning: Generative AI is mostly being used as a form of, admittedly, much better-looking, clip art.

Back in the 1990s, when clip art was all the rage, the people who used clip art in their documents, posters, slide decks, etc. were unlikely to have hired an illustrator, graphic designer, or artist.

There wasn't the budget, the aesthetic sensibilities, or the time.

Clip art was good enough.

Today, the very same people who are leaning on gen-ai to rustle up images on command are doing so for much the same reasons. It's fast, easy and does the job.

They probably wouldn't have hired a graphic designer in the first place either.

But clip art is not great art. (This is not a contentious statement.)

However, AI-generated images, videos and other content can look kind of convincing to our focus-starved modern minds. At first blush, they can look indistinguishable from ‘the real thing’.

Except when you give them any kind of detailed consideration.

Then, it all starts to unravel.

So it begs the question:

What does greatness look like in the age of AI?

The Architecture of Excellence

There is in an artform, a certain agreed-on framework through which the audience experiences the artwork: sitting down in a movie theater for two hours, picking up a book and reading the words on the page, going to a museum to gaze at paintings, listening to music on earbuds.

In the course of having that experience, the audience is exposed to a lot of microdecisions that were made by the artist.

Artforms that succeed—that are practiced by many artists and loved by many audience members over long spans of time—tend to be ones in which the artist has ways of expressing the widest possible range of microdecisions consistent with that agreed-on [framework].

Density of microdecisions correlates with good art.

– Neal Stephenson

In his essay on why ‘idea-having is not art,’ author Neal Stephenson, argues that the “categorical error made over and over again by idea havers is to mistake the actual production of the artwork—the making and fixing of the microdecisions—for mere drudgery that can, and ought to be, done away with.”

Idea haver: ‘I have a great idea for a movie/business/product. I'll tell you the idea and then you make it. We've split the profits 50/50!’

NS: What idea havers don’t understand is that it’s in the making of all of the microdecisions that the actual work of creation takes place, and that without it, the idea might as well not exist.

Artist > Density of Microdecisions > Audience

The way great art ‘works’ is that an artist who understands the constraints, conventions, and history of their art form communicates something of their own humanity to their audience via a high density of microdecisions that the audience can then interpret, consider, and, ultimately, be moved by.

AI skips over this ‘drudgery’ in a pre-fabricated fashion.

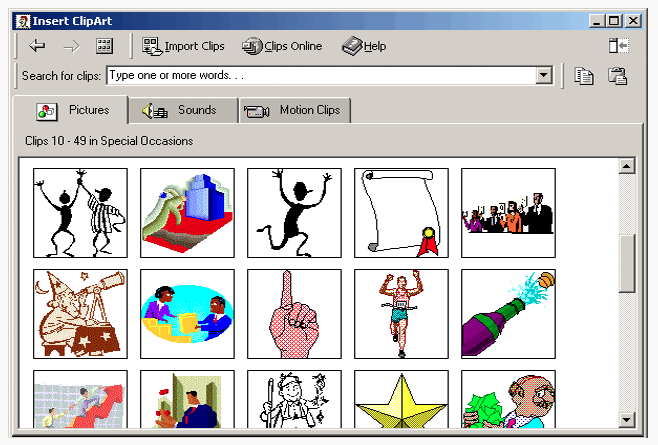

To this point, here's a classic interaction between Jerry Seinfeld and the Harvard Business Review, on the unrivaled success of Seinfeld:

You and Larry David wrote Seinfeld together, without a traditional writers’ room, and burnout was one reason you stopped. Was there a more sustainable way to do it? Could McKinsey or someone have helped you find a better model?

Who’s McKinsey?

It’s a consulting firm.

Are they funny?

No.

Then I don’t need them. If you’re efficient, you’re doing it the wrong way.

The right way is the hard way. The show was successful because I micromanaged it—every word, every line, every take, every edit, every casting. That’s my way of life.

Seinfeld has a high density of microdecisions.

That's why it's still “universally regarded as one of the greatest and most influential American television shows of all time.”

Clip art offers a low-grade of microdecisions.

The trouble with AI-generated content is that, although it has been trained on vast quantities of existing art, it only produces a statistical approximation of what art looks like, but the output is also devoid of microdecisions.

Much like clip art, there are no brushstrokes to be seen.

Great art = craft + humanity

The value of great art then comes from both the artistic craft of the artist, built up over thousands of hours of study and practice, and their humanity: the perspectives, experiences, opinions, tastes, creativity and imagination of the artist that propel each and every microdecision.

This is why, as filmmaker Kirby Ferguson puts it:

AIs will not be dominating creativity because AIs do not innovate. They synthesize what we already know. AI is derivative by design and it is inventive by chance.

Computers can now create but they are not creative.

To be creative you need to have some awareness, some understanding of what you're doing. AIs know nothing whatsoever about the images and words they generate.

Most crucially, AIs have no comprehension of the essence of art: living.

AIs don't know what it's like to be a child. To grow-up. To fall in love. To fall in lust. To be angry. To fight. To forgive. To be a parent. To age. To lose your parents. To get sick. To face death.

This is what human expression is about. Art and creativity are bound to living, to feeling.

Art is the voice of a person. And whenever AI art is anything more than aesthetically pleasing, it's not because of what the AI did. It's because of what a person did.

Art is by humans, for humans.

— Kirby Ferguson

What then shall we do?

Double down on our humanity and our craft.

How to Become Great: Get Good at Something

How do I become a great editor?

Cut daily.

(No, this hasn't all been leading to a sales pitch.)

Cut/daily is called Cut/daily because of this quote from Lori Jane Colman ACE and Diana Friedberg in their excellent book, Jump Cut.

It takes time, tenacity and a true passion for discovering the multi-layered talents that an editor possesses – and it takes commitment.

You should be cutting every day.

The path to mastery happens one step at a time, day after day, mile after mile, hill after valley, come rain, come shine, when you feel like it and when you don't.

You have to cut daily.

If you watch the Digital Spaghetti video above you will see three accomplished storytellers geeking out over how great Every Frame a Painting is.

It's an object lesson in:

a) what great editing looks like

b) the joy of unpicking all those densely packed microdecisions.

So how do you become great?

- Accept your mediocrity

- Practice

- Fall in love with the process

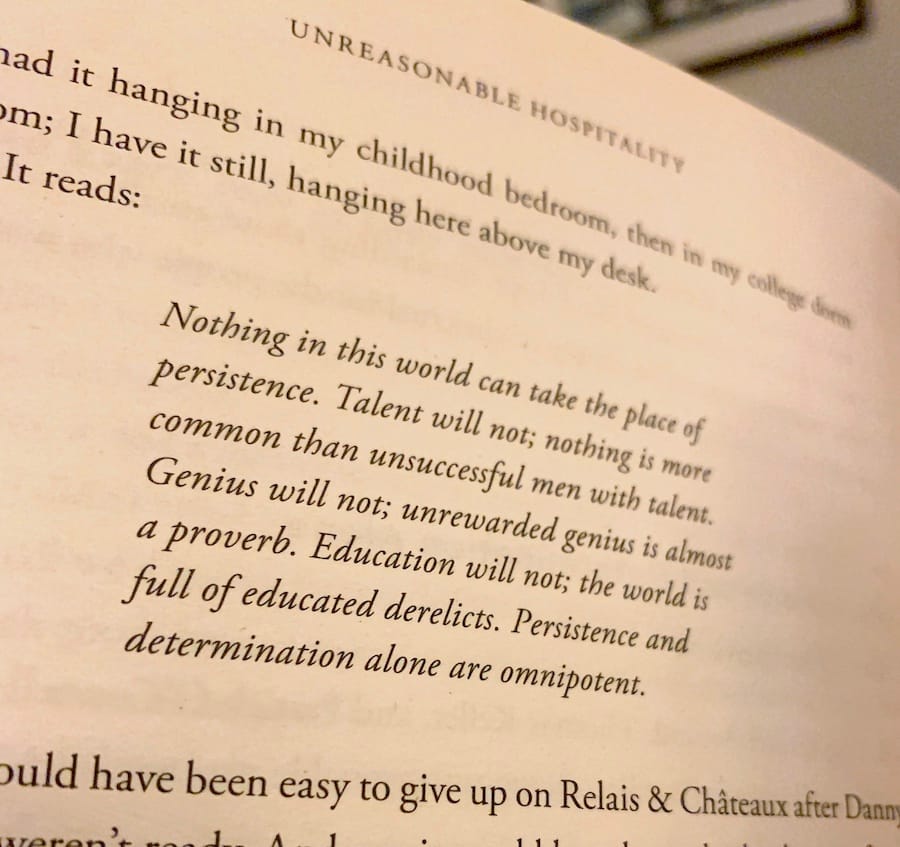

Persistence is all that matters

In the beginning, you will suck and you will know it.

But that's OK.

As Ira Glass famously described, at the beginning of your creative journey, your taste will exceed your abilities.

The only way to close that gap is to do a lot of work.

The most important possible thing you could do, is do a lot of work, do a huge volume of work... It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions.

— Ira Glass

Or, as Jerry Seinfeld responded when asked what he would do if he were ever to teach a class on becoming a comedian:

I would teach them to learn to accept your mediocrity.

You know, no one's really that great. You know who's great? The people that just put tremendous amount of hours into it.

It's a game of tonnage.

So how do you become great?

- Accept your mediocrity

- Practice

- Fall in love with the process

Have fun along the way

The only way to become excellent is to be endlessly fascinated by doing the same thing over and over. You have to fall in love with boredom.

– James Clear, Atomic Habits

I found this quote in an essay by Steph Smith called ‘How to Be Great? Just Be Good, Repeatably’ which she wrote after noticing that “each month 1000 people search ‘how to be great,’ 260 people search ‘how to become perfect,’ and 2400 people search ‘how to be the best.’”

In the essay, she argues that:

- Greatness is not instantaneous

- Greatness is earned

- Consistent, deliberate practice is the key to achieving “greatness” in any field, particularly in creative pursuits.

So finding a repeatable way to incrementally improve your abilities is the path to becoming great.

To become a great editor you have to cut daily because that's the way you'll get a little bit better every day.

Yet, to sustainably edit every day, you have to actually enjoy editing.

You have to enjoy the organising, watching, absorbing, planning, creating, experimenting, deleting, refining, demolishing, re-building and rearranging process.

The process that will basically be the same process in a year from now. In 10 years from now: the making and fixing of all those microdecisions that lead to great art.

When you can spend your days loving what you do, regardless of the outcome of that effort, you'll at least have had fun along the way.

And you'll probably do it all again tomorrow.

You, Me, and The AI Future

So, where does all of this leave us?

To become a great editor in the age of AI you just need to keep doing what you're doing.

- AI cannot make great art because “AIs have no comprehension of the essence of art: living.” So you have that in your favour.

- And to be a human being who makes great art you just have to keep creating until you get there.

So don't give up.

Great art = craft + humanity.

But won't the generative AI apps just get better and better, and slowly take over the world?

Isn't your clip art analogy flawed in that, unlike pixelated bitmap art from the 1990s, AI's output is so rapidly improving that all its problems will be swallowed up by inevitable technological progress?

No.

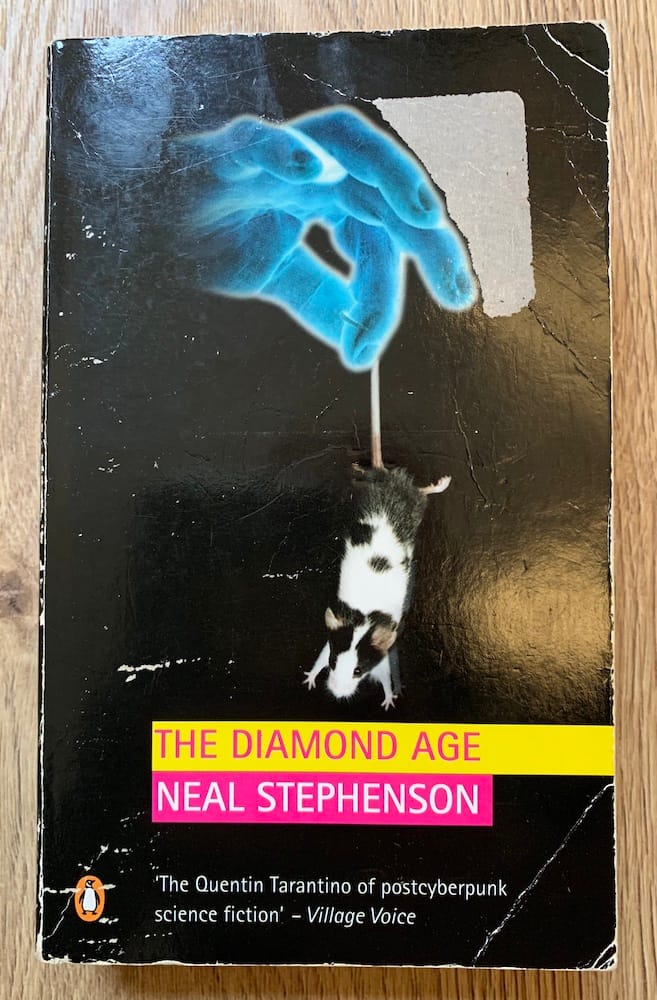

30 years ago, Neal Stephenson published what feels to me like a very prescient book called The Diamond Age, or a Young Ladies Illustrated Primer.

Set in the future where nanotechnology has made it possible to ‘print’ anything instantaneously in a matter compiler (M.C.) from buckets of hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, etc., there is a group of people who have reverted to making things by hand.

When you can fake anything, real things become more valuable.

“My name's Rita, and I make paper.”

“You mean, in the M.C.?”

This seemed like an obvious question to Nell, but Rita was surprised to hear it and eventually laughed it off. “I'll show you later. But what I was getting at is that, unlike where you've been living, everything here at Dovetail was made by hand. We have a few matter compilers here. But if we want a chair, say, one of our craftsmen will put it together out of wood, just like in ancient times.”

“Why don't you just compile it?” Harv said. “The M.C. can make wood.”

“It can make fake wood,” Rita said, “but some people don't like fake things.”

“Why don't you like fake things?” Nell asked.

Rita smiled at her. “It's not just us. It's them,” she said, pointing up the mountain toward the belt of high trees that separated Dovetail from New Atlantis territory.

Light dawned on Harv's face. “The Vickys buy stuff from you!” he said.

Rita looked a little surprised, as if she'd never heard them called Vickys before. “Anyway, what was I getting at? Oh, yeah, the point is that everything here is unique, so you have to be careful with it.”

— The Diamond Age

Creative technologist Katie Hinsen shared similar perspectives in a wide-ranging conversation with colorist Patrick Inhoffer on the impact of AI on the creative industries.

“We're all creative technologists because we use technology to make art.

And whether that technology is film strips or whether that technology is computers, that's what we do. We manipulate science to make art.

There is one thing I can say 100% for sure is that computers, by their very nature, cannot be artists, cannot be creative, but they can be a tool to make art.

The other thing I can say, having been very deep under the hood of a number of these AI companies, is that they all want to make money.

And they want to make money off artists who are the users of those tools. They're not going to put those users out of business. They're going to start by at least making things that we want.

But I also think that audiences, especially when these technologies start to impact people, the middle class, everyday people, are going to start seeing the value in handmade things.

So, as people start seeing that there is less value in stuff that is generated by AI because they can just do it for ‘free’, you're going to see that there's more value in the stuff that is generated by people and that feels very human-made.

— Katie Hinsen

Intuition, not knowledge

Lastly, real artists break the rules at the right time.

In the Editing Podcast's conversation with editor Joe Walker, he breaks down a moment in Dune Part 2, in which Joe deliberately breaks one of the ‘rules’ of film editing grammar.

He crosses the line.

And he does so for good reasons. He cuts across it to harness the best performances but also to enhance a pleasing jump scare.

As editor Michael Kahn says “Cut from intuition, not knowledge.”

So, as Joe Walker—undeniably a great editor—demonstrates, real artists (like you and me in the making) can develop our editorial intuition through deliberate practice until we too can break the rules knowingly, to surprise and delight our audience, ultimately making microdecisions that an AI algorithm couldn't fathom because they lie outside of the realm of statistical probability.

One Final AI-Friendly Thought

As a creative artist, you have valuable skills and a unique perspective on life that imbue your work with meaning and can delight audiences for years to come.

I hope you have many satisfying days of deliberate practice, plying your trade, honing your craft and making great art.

But you absolutely should learn as much as you can about AI.

If you want to travel to new places, you have to learn new languages.

AI is a new tool for creative artists to harness. And that will take some practice.

Personally, I think it's all fascinating. It feels like the beginning of the internet all over again—a new playground to explore.

Play with the new tools, learn new things, understand the true value of utility AI.

AI will (eventually) change everything, but the fundamental core of what you have to offer as a creative artist will not.

So remember, keep going until you get good at something and cut daily.

Take This Further

Citations and other rabbit holes to fall into:

- Idea having is not art – Neal Stephenson

- Seinfeld is universally regarded as one of the greatest and most influential American shows of all time. – Wikipedia

- Everything is a remix – This four-part series is essential viewing for any artist looking to understand creativity: Copy, Combine, Transform.

- “Always double down on 11.” – Swingers (1996)

- How does an Editor think and feel – Every Frame a Painting + Digital Spaghetti Lovefest

- Why your taste exceeds your abilities – Ira Glass

- Three reasons why Cut/daily is called Cut daily.

- How to Be Great? Just Be Good, Repeatably – Steph Smith

- Joe and the Worm – a masterclass of microdecisions unpacked.

Cut/daily Complete Access

Get lifetime access Cut/daily's complete archive of over 430 Post-Production insights, plus exclusive discounts and referral offers!